When the bones of the early shielded dinosaur Scelidosaurus were uncovered in 1858 in west Dorset, England, they involved the principal complete dinosaur skeleton ever recognized.

Yet, aside from cursory papers by spearheading British paleontologist Richard Owen in 1861 and 1863 that not completely portrayed its life structures, Scelidosaurus was for quite some time dismissed in spite of the milestone idea of its revelation.

That has now changed, with the principal careful assessment of its fossils finally giving Scelidosaurus its due — indicating that it had unique anatomy and determining its place on the dinosaur family tree.

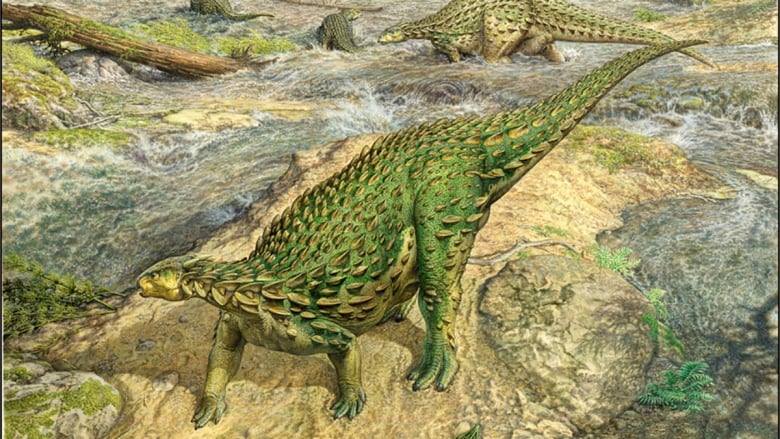

University of Cambridge paleontologist David Norman said Scelidosaurus, which lived around 193 million years back, was an early individual from the developmental heredity that prompted the dinosaur bunch called ankylosaurs. Ankylosaurs were so vigorously shielded — some even employed a hard club toward the finish of their tails — that they are dubbed the tank dinosaurs.

There has been a long-running debate over whether Scelidosaurus was ancestral to another group called stegosaurs, known for the bony plates on their back.

Scelidosaurus was a 14-metre-long, four-legged plant-eater covered in spiky, bony armour. Its face was plastered with horny scutes, a bit like the face of a marine turtle. It was a moderately agile animal with defensive spines to deter predators.

“It has a lot of fascinating anatomies,” Norman said.

Scelidosaurus is among the earliest-known members of an even-larger dinosaur grouping called ornithischians and provides new insights into this group’s origins.

This particular individual was probably the victim of a flash flood and drowned in the sea, with its body becoming buried in sediment.

“This animal was discovered at a crucial time in the history of dinosaur research. It was given to the man [Owen] who invented the name ‘dinosaur’ in 1842 and gave him a chance to at last demonstrate what dinosaurs really looked like.”

“Up until that moment dinosaurs had only been known from scraps of bone and some teeth,” said Norman, whose fourth research paper describing Scelidosaurus was published this month in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society of London.

“Curiously, Owen did not describe it adequately and it has lain in the collection of the Natural History Museum in London — researchers knew of it by name, but it was not at all well understood,” Norman said.

Photo credit: John Sibbick/Handout via REUTERS

News source: Reuters